Woman, a Frog and a Devil

A review of Olga Tokarczuk's new novel The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story

Apologies first and foremost that this is so late - I have been low key ill for over a week now and it’s really getting on my wick/tits/last nerve - all the things. Hope you like it and, seriously, buy this book.

To see everything we must look beneath them, let ourselves be momentarily blinded by the grey haze

We start Olga Tockarczuk’s new novel The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story addressed as a collective, a ‘we’, brought in and immediately made a voyeur. Throughout the novel we spy as readers, whilst knowing there’s foreshadowing in the narration that we’re not privy to, basking in a blindness and an uncanny ‘haze’.

This subtle and sophisticated formal flair is maybe one of the ways in which Tokarczuk remains contemporary whilst nodding to tradition; specifically, the novel is a take on Thomas Mann’s 1924 novel The Magic Mountain, recasting it and reinventing it beyond homage but not quite a straight retelling. The main things The Empusium shares with Mann’s novel are character and setting. Both have patients in a sanitorium, high up in the mountains, being treated with various ‘cures’ for tuberculosis.

‘Character and setting’ might seem like everything but the formal weirdness, the way in which an omniscient voice pierces the narrative and then disappears for whole sections of the novel, refracts it and makes it new. Some of the characters are real-life historical figures, Hermann Brehmer for example, who actually opened the first ‘open-air cure’ sanitorium to treat tuberculosis in Görbersdorf (now Sokołowsko). Somehow this layering of histories, human and literary, creates something new and exciting in a way that feels like writerly magic.

They also both take place in the build up to the Great War, complex international relations and the character of countries woven into the dialogue with unparalleled skill. There’s no fusty interludes here in which the reader feels lectured to, no long monologues from one of the men in order to squeeze more national character in via one of the protagonists. Though the observations from Wojnicz and others espousing the personality of different countries can feel tiresome, it’s because the men themselves are tiresome, that this sense of national identity is on the brink of shifting and collapsing. Tokarczuk’s characters are not just a product of their time, their conditions, their illness, but through interludes like these their psychogeography is explored and they are revealed to be an equal product of their landscapes and locations.

As we know, however, the most interesting things are always in the shadows, in the invisible

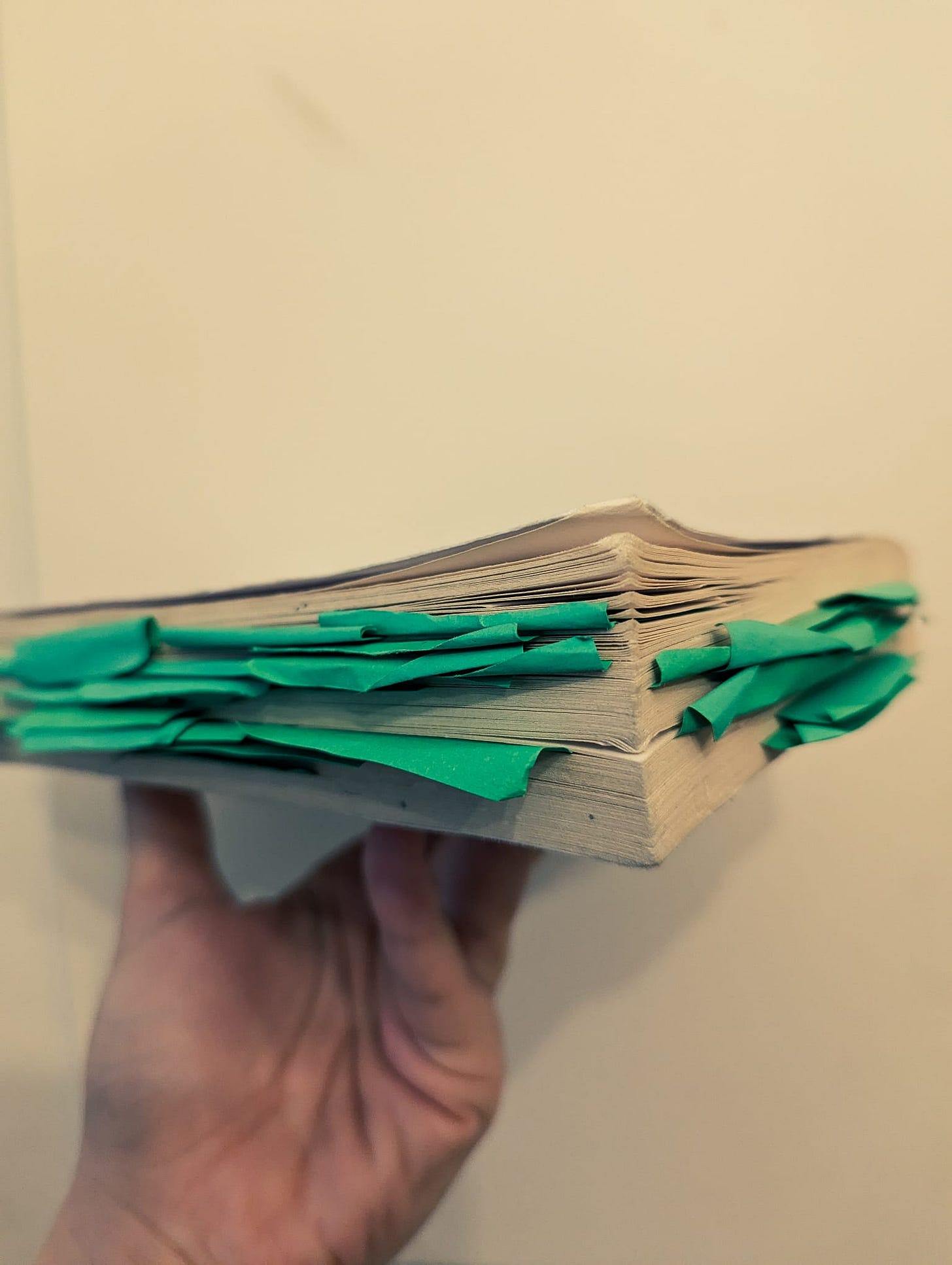

Even upon second reading, the book now creased, thumbed, greyed, and peppered with the detritus from the bottom of my bag, I couldn’t tell you exactly how she achieves that tradition without derivative. I also couldn’t tell you how she’s managed to write a novel that engages with so much without feeling dense or like a box-ticking exercise.

For example, it seems at first that the main thrust of the novel will be feminist. Sections of the dialogue are directly taken from some of the most prominent male academic and literary voices of the past, revealing their misogyny in the process. At the end of the book we learn that some of the more brazen, caricatured perceptions of women in the novel were actually directly sourced from some of our most celebrated authors: ‘misogynistic views on the topic of women and their place in the world are paraphrased from text by’ a list of authors including, but not limited to, William S. Burroughs, Joseph Conrad, Charles Darwin, Sigmund Freud, D.H Lawrence, Freidrich Nietzsche, Jean-Paul Sartre, William Shakespeare and W.B Yeats.

We are told that ‘whatever they had been talking about earlier, later on it was bound to come down to the same thing – women [...] Wojnicz had noticed that every discussion, whether about democracy, the fifth dimension, the role of religion, socialism, Europe, or modern art, eventually led to women’. But, as the novel goes on, this illustration of misogyny is made just one strand of a complex theoretical tapestry that swings between formal and philosophical playfulness.

This is similar with the genre: at first it may feel like a traditional horror, in its setting, in its having actual “monsters” in the end (at least deemed so by the men), in its shock and the small psychological jump scares that occur when Wojnicz explores the house, especially the attic, in more depth — it is a very visual novel. But it also feels slow and doesn’t show its hand too early, building dread instead of showing anything too early on, even if the hints are a little heavy handed at times. Though there is this voyeuristic voice it’s never quite affirmed as a malicious presence, it seems more like just an omnipotent perspective than something that wishes Wojnicz harm, complicating even the sense of dread.

The title The Empusium comes from the ‘Empusa’ from Aristophanes’ The Frogs, a shape-shifting female temptress who taunts Dionysus and Xanthius on their way to the underworld. This is a play quoted by Herr August in the novel as they traverse the surrounding woodland and argue, once again, about women. This becomes another interesting way in which Tokarczuk layers histories and brings tradition through, around, over the contemporary. Here we have a feminist reinterpretation of a German nobel-prize winner’s novel, its title, in turn, from the Greek literature some of the characters defer to in legitimising their views on women. The novel becomes an historical microcosm, dealing with the past whilst reflecting it in increasingly uncanny and unnerving ways in the present.

Like I said, how she writes something this fresh, taking several canonical literary signposts and managing to make them feel fertile and rich and new, is something of a mystery. I don’t think I want to know. Maybe this would be like learning how a magic trick works – I’m happy to enjoy the prestige without having it explained.

No, we do not regard it as an obsession, at most as innocent oversensitivity. People should get used to the fact that they are being watched.

I could spend the rest of this review chronicling all of the ways in which the novel engages with different ‘-isms’ and the different ‘-logical’ perspectives. What first seems to be straightforward in its ideology, overwhelmingly feminist in its preoccupations, soon grows to include theology, ecology, both the scientific and the metaphysical and, ultimately, queerness in all of its forms.

This is an element that I won’t explore too deeply because I don’t want to reveal too much. However, I will say that it’s one of the most beautiful parts of the novel; the way in which queerness, not just within the strictures of sexuality but the way in which existence is queered, humanity is queered by the ecological, and the body is queered by illness, follows Wojnicz’s stay at Görbersdorf.

We know that when Wojnicz is younger, out of the sight of his father, he subtly resists his father’s prescribed ideas of masculinity:

whenever he was alone and out of the reach of his father’s discipline … he would wrap his naked body in a satin tablecloth edged with a soft fringe and, feeling how blissfully it brushed against his thighs and calves, he would think how wonderful it would be if people could go about in tablecloth tunics, like the ancient Greeks.

Even that which his misogynistic fellow patients cling to in defending their hatred of women is queered and complicated by Wojnicz here. He remains a complex, soft, liminal character, a celebration of the ‘grey haze’ from the start of the novel, a testament to the places at which we blur, with non-human nature, with others, with art, with god and, ultimately, with the categories we create to pretend we are more solid and rigid than we actually are.

This novel is absolutely gorgeous and you really should buy it. Thanks so much to Fitzcarraldo for the review copy - you can buy it directly from them here or from a lovely Liverpool-based independent shop here.