If You Have to Ask What Jazz Is, You'll Never Know What it Is

A review of Wesley Brown's Tragic Magic

Catherine Lacey recently wrote in her Substack, Untitled Thought Project (which I would highly recommend if you haven’t already subscribed), about George Eliot’s Middlemarch. She writes that:

In general, classic literature is a great way to see how unoriginal our mistakes are, and it accomplishes this in a way that contemporary books typically can’t. The manners, laws, clothes, customs, language, hierarchies, freedoms, and restraints are all different and yet the basic ignorances and pitfalls lurking in the human spirit remain. When reading such stories set in the present, it’s easy for a reader to get hung up on the details, to over-interpret, to make too many associations and assumptions about qualities in the characters and settings that are ultimately insignificant.

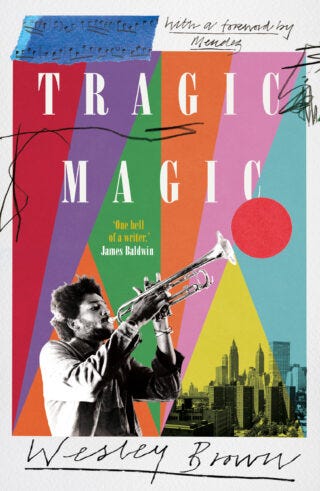

My experience of Tragic Magic by Wesley Brown, recently republished by Daunt Books, felt the same somehow. Though the novel is certainly not classical and doesn’t have the same amount of distance and remove culturally, customarily or socio-politically from our own times, it does perform this reminder, sadly contextualising the present pitfalls of masculinity and resistance against it within a story written almost fifty years ago.

The novel follows Melvin Ellington, a jazz musician living in New York, on the day he’s released from prison for being a conscientious objector during the Vietnam war. What unfurls throughout is a chronicling of Melvin’s political perspective, the influence of jazz on language, gendered insecurity and its influence on the women who orbit this particular generation of men. At times a little disjointed in its attempt to encapsulate so much, the result is still a poetic and beautiful portrayal of a very short time, like a jazz Ulysses, wandering the city, diagnosing the fragility of its inhabitants and the political roots of that fragility.

At first, all of these threads fail to cohere around Melvin who, for the first half of the book, feels more like a mirror for other people and slightly empty as a result. However, this is steadily filled by earlier and earlier flashbacks that increasingly permeate the prose in the second half. Whilst we’re learning about his time in prison at the start of the novel, and as he acts the flaneur around a New York suburb, it’s language that takes centre stage rather than Melvin himself. Brown subtly, initially, contextualises Melvin through jazz rather than his activism. Little descriptions interrupt the prose and, though they sometimes feel misplaced or out of sync, this reads as deliberate from Brown, an attempt to make the novel disjunct at the sentence level, mimicking atonal bebop shifts from one phrase to the next:

Scatology is a branch of science dealing with the diagnosis of dung and other excremental matters of state. Talking shit is a renegade form of scatology developed by people who were fed up with do-do dialogues and created a kind of vocal doodling that suggested other possibilities within the human voice beyond the same old shit.

Moments like these, despite interrupting our introduction to the character, and seeming a little like Brown talking to us rather than Melvin, nonetheless sing on the page. Out of place or not, they’re just a pleasure to read. Here, though Melvin’s life is yet to be fleshed out, we’re introduced to voice and sound, two of the key themes of the novel.

When comparing penis size in the shower in prison, the jazz-like language escales from ‘white dudes sport drawed-up pee shooters’ to ‘the final comedown in the test of manhood between black and white being determined by the one who can get his rizz-od as hizz-ard as a rizz-ock at a mizz-oments nizz-otice.’

Sometimes, like here, the breakdown of the language to its verbal and oral level veers into being slightly too literal, grating a little. The determination to make it sound like jazz hinders the meaning at times. But when sound is the content, and not just the focus of the form, this is when Brown’s prose really shines. Sections that are rhythmic and alliterative but slightly more restrained than those replete zeds in the above quote, make the writing musical without trying too hard:

Those catnaps with my father made those words the handle that cranked out my first clear sounds. His snoring was filled with the lingo that a father must pass on to his son if his son is to carry on the family tongue, get a grip on his own voice, and not lose himself in babbling.

This very small and subtle excerpt really encapsulates all of the best things about this writing: those repeated L’s, intergenerational and socialised masculinity, voice as both communication and musicality, and the desperate attempt from a man to combine all those things to connect with other men.

The other strongest thread throughout is how gently a disaffected generation of Black men is portrayed by Brown, specifically the sociopolitical attitudes towards the Vietnam war. When he first arrives in prison, another person who’s incarcerated explains Melvin’s place to him:

They figure that with what you got going or yourself you should a been able to scheme your way out a coming to jail. And since you didn’t, all that education you got ain’t worth a damn. They figure they got more of a beef with society than you do.. They never had the opportunities you had. So you not going along with whitey’s program don’t cut no slack with them.

This is one of the most prescient things about the political landscape depicted: the individualised experience often supersedes the collective one. To these other men, Melvin may as well be white because of the privilege he received through education; the things he was fighting against are presented as philosophical and removed from the lived reality of individual Black people in America. This is hauntingly familiar in a time when individual liberties, specifically male liberties and the purported “infringement” upon them, is divorced from any ideological context. Instead of solidarity, individual oppression is siloed and in constant competition with that of someone else’s and far right governments and internet weirdos have convinced several generations of men that the reason they’re disenfranchised is because of their marginalised and oppressed neighbours. This is best encapsulated by Baldwin in a letter to Angela Davis: ‘if they take you in the morning, they’ll be coming for us that night.’

Looking at something written in 1978 that discusses the Vietnam war, and the reaction of a disenfranchised Black masculinity towards it and towards one of its objectors, haunts the present in surprisingly sharp ways. Vietnam was the first US war in which Black and White troops were not formally segregated. The processes that determined eligibility were racist to begin with but got even worse as drafting of Black soldiers increased dramatically with Robert McNamara’s Project 100,000. The project lowered the mental and medical standards by which soldiers were drafted meaning that huge numbers of Black men and working-class White Southerners were overrepresented in the scheme. In fact, Black soldiers made up around 40% after three years of the project, even though they only made up 11% of the US population.

In short, Black men were disproportionately represented in the US forces during Vietnam and they continue to be disproportionately represented in its prisons. The duality drawn between these two things by Melvin’s fellow prisoners in Tragic Magic is subtly but expertly illustrative of an abstract disenfranchisement: in their eyes, someone privileged enough to be able to look over there to Vietnam, must have had it pretty sweet at home. Melvin’s resistance is seen as making him ‘no different than a white boy’.

This localisation manifests throughout the novel in the traversing of the city, the interiority of Melvin, the tightness of the prose and the temporal vignettes. This is another way in which the jazz comes through too. The flash backs that take place are often sensorially triggered and sudden:

These security measures reminded me of the day I approached another building that had U.S. Penitentiary chiseled into the brick…I am among about forty men being led inside the wall. Once inside, we strip, give the hacks a peep show up our assess, and change into prison-issue clothing.

The time shifts like the tempo, which etymologically comes from ‘terrestrial’, the ‘worldly’ and the world in which Melvin inhabits is shaped by the language that’s both subject and medium in the novel. Though scattered at times, it is a full and sensorially rich world to read.

Tragic Magic is available now from Daunt Books Publishing - order from your local independent here.